The Spectral Generator

The most distinctive part of the Manatee’s sound resides in its Spectral Generator. But in contrast to the VA-like sub oscillator, we might not have much intuition around what the generator’s parameters are or how they shape its output. So let’s tear it apart to see what makes it tick!

The GEN Screen

First thing’s first: let’s check the “Balance” knob in the Manatee’s “sources” section. This controls the mix between the spectral generator and the sub. Seeing as we’ll be playing with the spectral generator, turn it all the way clockwise so that’s the only thing we hear.

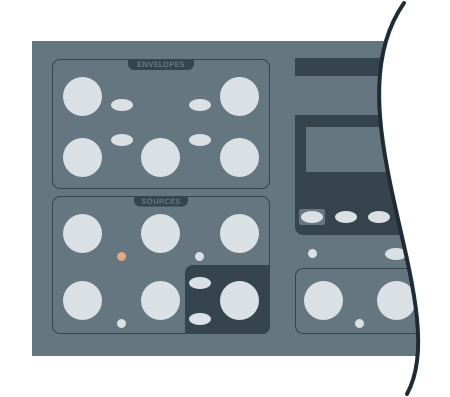

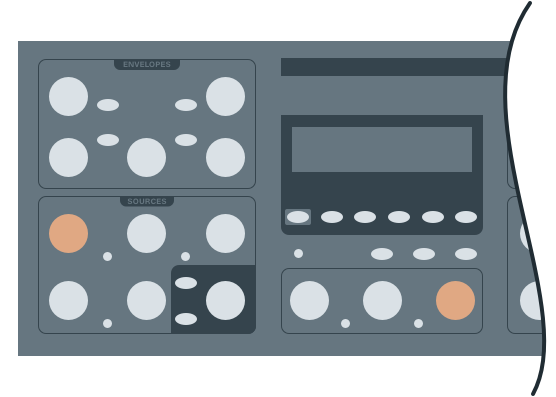

Next, we’ll want to jump to the Spectral Generator’s screen. If it’s not currently up, we can jump to it by clicking the tiny GEN button in the sources section (see: fig 1.1). Once displayed, the screen will look something like:

GEN WAV BASIS

▇▄▃▁ ◜◝◟◞ EXPONRG

Taking a look from left-to-right, we first see GEN, which is the title of the page and has a pictorial representation of the current spectrum below it. Next comes WAV, which shows the waveform which will “play” the spectrum. And finally BASIS, which is the name of the chosen spectrum.

If you’re confused about what all this “spectrum” and “wave” stuff is, I go into much more depth about it in my post on spectral synthesis. But the gist is: a spectrum is a bar graph where each column represents a step of the harmonic series, the height which determines how loud that particular harmonic should be played.

That’s the image we’re seeing in the lower-left of the GEN screen. It’s an eight-bar spectrum representing the harmonics the spectral generator will play.1

BASIS Instinct

The Manatee contains 18 preset spectrums2 for us to use as the basis of our sounds. To cycle through these, we change the BASIS parameter — which we can do either using the dedicated SPECTRUM knob or the third of the value pots (see: fig 2.1).

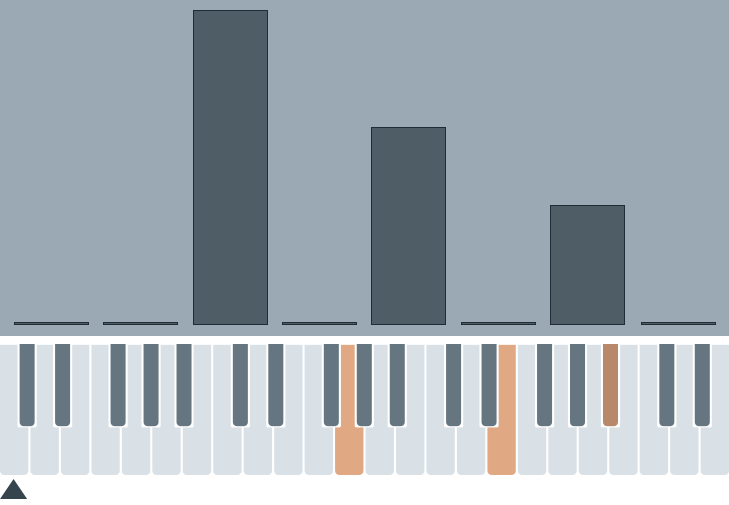

The very first of these preset spectrums is called PART, but we’re going to skip that for now.3 Instead, let’s begin with the basis called ROOT. We can see only one of its bars is filled in. That means it will only generate one harmonic. And it’s the first one, which means the harmonic generated will be 1× the frequency of the note played. So, for the ROOT spectrum, if we play a C on our keyboard, a C will be generated (see fig 2.2). It’s a pretty simple sound.

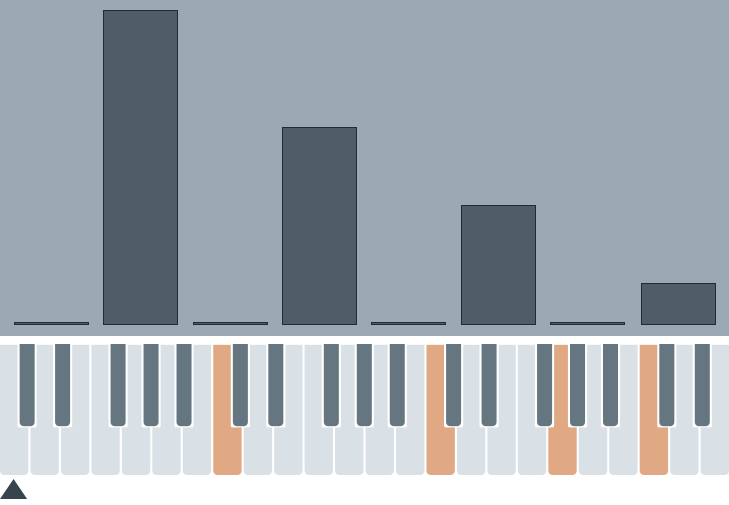

But what about the next basis? It’s named EVEN, and here we see every other harmonic is filled in, starting with the second. In other words, this will generate even harmonics at 2×, 4×, 6×, and 8× the original frequency. So if we play a C1 on our keyboard, a C2, C3, G3, and C4 will be generated, each softer than the last (see: fig 2.3). This spectrum mostly emphasize octaves of the fundamental resulting in a more “full”, pipe-organ-like sound.

Note the fundamental (that is, the first bar) of the EVEN spectrum is not filled in. That means it doesn’t actually generate the note we play on the keyboard. Indeed, because the biggest bar of the EVEN spectrum is the second one (which is 2× the fundamental pitch), it sounds like it’s playing an octave higher than the key we press. Cycling through other preset spectrums on the Manatee, we can see most of them omit the fundamental like this.

Why leave out the fundamental when that frequency is so important to anchoring the pitch of the sound? Because that’s a job the Sub Oscillator can handle. By default the sub will always play at the fundamental pitch. And with the help of the BALANCE knob, we can easily mix in the exact amount we want in our patch. Having that kind of fine-grained control over the strength of the fundamental is really useful when shaping additive sounds.

Moving on, let’s look at the ODD spectrum (see: fig 2.4).

We can see it, too, lacks the fundamental. But excluding that, all the odd harmonics are accounted for. Thus, when played, it will generate harmonics at 3×, 5×, and 7× the original frequency. This gives it a slightly hollow, almost square-like sound, especially when mixed with the sub.

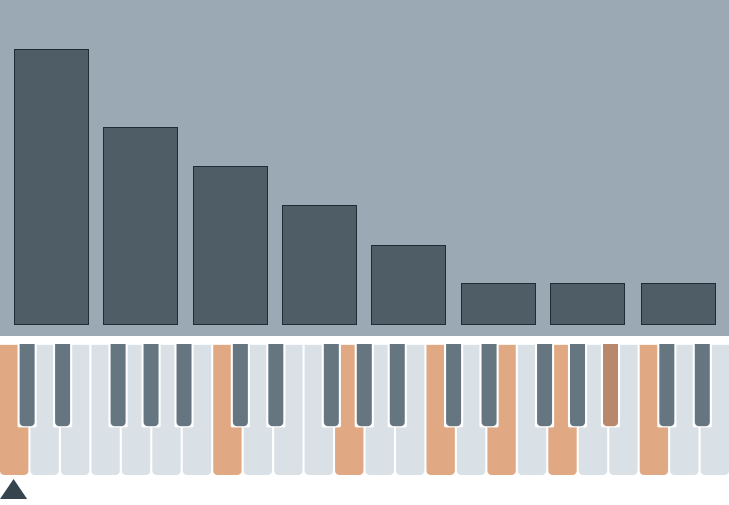

Finally, let’s check out EXPONRG.

It has a value for every bar, and thus generates every one of the first eight harmonics (see fig 2.5). It is, then, essentially of a combination of ROOT, EVEN and ODD. The result is a harmonically rich, buzzy, sawtooth-like sound.

And so on. We can get a sense for the sound any spectrum will generate just by looking at its shape, figuring out what harmonics it will generate, then imagine “playing” those harmonics together.

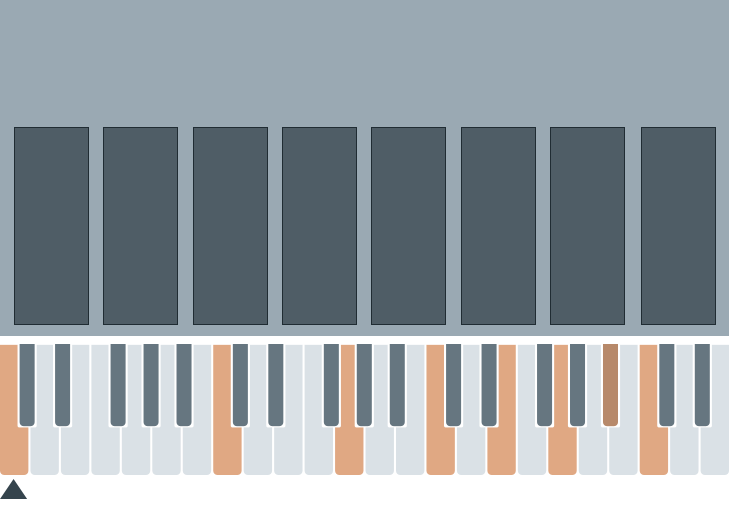

Of course, how loud those harmonics are “played” in relation to one another matters a great deal. As an exercise, compare EXPONRG (fig 2.5) with the FULLBAR spectrum (fig 2.6). Both spectrums generate all the same harmonics, but EXPONRG plays them successively softer while FULLBAR plays them all equally loud. We can hear the large affect this has on the sound by flipping between them. EXPONRG sounds more natural and “whole”, while FULLBAR sound more harsh and complex, like a drawbar organ.4 The comparative strength of those upper harmonics has a lot of influence on the sound!

Riding the WAV

Of course, it’s not just harmonics and their levels that define the character of a sound. The thing used to actually play those harmonics is pretty important, too. And that’s where the WAV property comes in. The spectral generator uses the waveform selected under WAV to play each of the harmonics in the spectrum.5

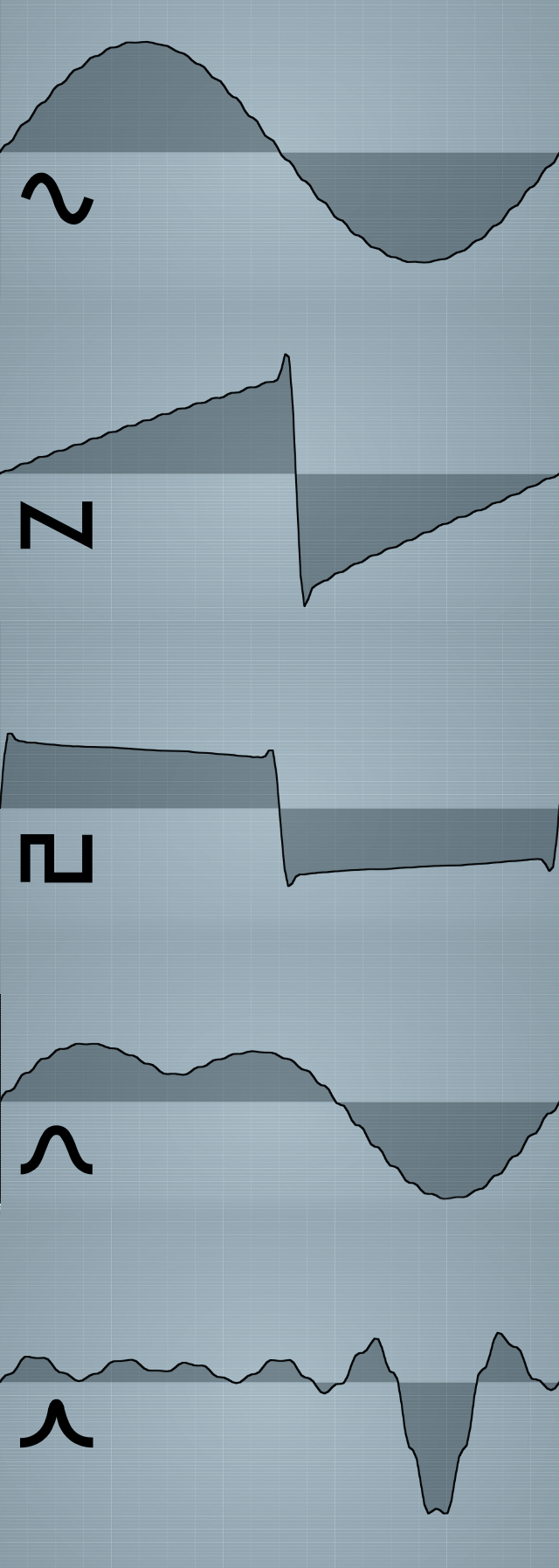

We can cycle through the WAV options by repeatedly clicking the GEN button (see fig 1.2) or by using the second of the three value pots if the GEN screen is already visible. There are little icons for the waves printed onto the Manatee’s case, and a tiny representation of the selected wave is displayed on the screen. But they’re small and can be a hard to decipher. So I ran each through an oscilloscope to get a better idea of how they look (see fig 3.1).

There’s not a lot unexpected about the general shapes of the first three. They look like a sine, saw, and square, respectively. But it’s worth highlighting the wavy, 8bit-ish, high-frequency distortion in the sine and saw — especially when playing lower notes. I find this bit of character charmingly chiptune-esque, but if it’s not your cup of tea, you can smooth it out by closing the HPF a hair. Or, since it’s not present in the Sub Oscillator and disappears at higher frequencies, you can use the sub to hold down the fundamental as discussed above to avoid it altogether.

The last two shapes are less common, so harder to guess how they will sound. The one with the bell-curve icon strikes me as a mellow saw. Like, something just slightly more buzzy than a triangle. The final one with the sharp peak for an icon feels like an impulse wave. Very buzzy like a saw, but with more emphasis on the high-end.

So these waveforms cover a lot of ground, sonically speaking. Even after carefully selecting our spectrums, there’s still a bunch of variation in character we can apply just through our choice of WAV.

Generating Spectrums

So putting it all together, when a note is played the Spectral Generator looks at the spectrum selected by BASIS on the GEN screen. Then, for each bar in that spectrum:

- It plays a wave with the shape selected under

WAV - …with a frequency determined by the bar’s position (1× for the first, 2× for the second, 3× for the third, &c.)

- …at a level determined by the bar’s hight.

It doesn’t seem that complicated once we’re able to break it down like this. In some ways, the Spectral Generator is just a fancy chord generator that only plays overtones. Sure the results are harmonically interesting — sometimes to the point of being distracting. But now that we understand it, is it not a touch… boring?

That’s because there’s still a whole other facet of the generator left for us to tackle: the various mods macros that provide motion and interest to our base spectrums.

But those live on the second page of the GEN screen, so will have to wait for the next post.

-

Some synths, particularly those classics with a focus on additive sounds, can offer 3–4 times the number of harmonics to work with. The eight-harmonic spectrum of the Manatee is definitely a lot easier to manage and take in at a glance, but is it missing out by not offering more harmonics?

It depends on what one’s trying to accomplish, of course. But remember the eighth harmonic already represents a frequency 8× the fundamental — that’s three octaves up. And above that, frequencies are only getting higher and more closely spaced. It’s hard to add much of those upper harmonics without making a patch sound harsh and digital.

So in general, I find the Manatee’s eight-harmonic spectrums to be a good compromise between simplicity and sonic breadth for a machine focused on sound design. ↩︎

-

Spectra? ↩︎

-

PART is actually a completely user-editable spectrum that gets saved with the patch. Whcih is really cool! But also a whole other topic for a whole other day. ↩︎

-

And this isn’t a coincidence. The drawbars on an organ are directly comparable to the bars of our spectrum — each is responsible for adding more of a particular harmonic to a sound. Thus, the “FULLBAR” spectrum is equivalent to “pulling out all the bars” of a Hammond. Organs were the original additive synth! ↩︎

-

Classically, this was done with a sine wave. Because a sine is all pure fundamental without any higher harmonics, it can “reconstruct” each bar of a spectrum without adding any of its own overtones to the mess.

Of course, the “mess” created by overlapping overtones of harmonically rich sounds is sometimes called “music”, so the Manatee happily provides us with an assortment of waves for the job. ↩︎