Steampipe and the Reverb Mix

When adding FX to a signal chain, there’s always the choice of how to route it. The Steampipe’s main reverb control is labeled “MIX”, which might lead us to believe they’ve chosen to wire it as an insert. But actually it’s a send, and this is a Good Thing. I’ll explain…

Inserts vs. Sends

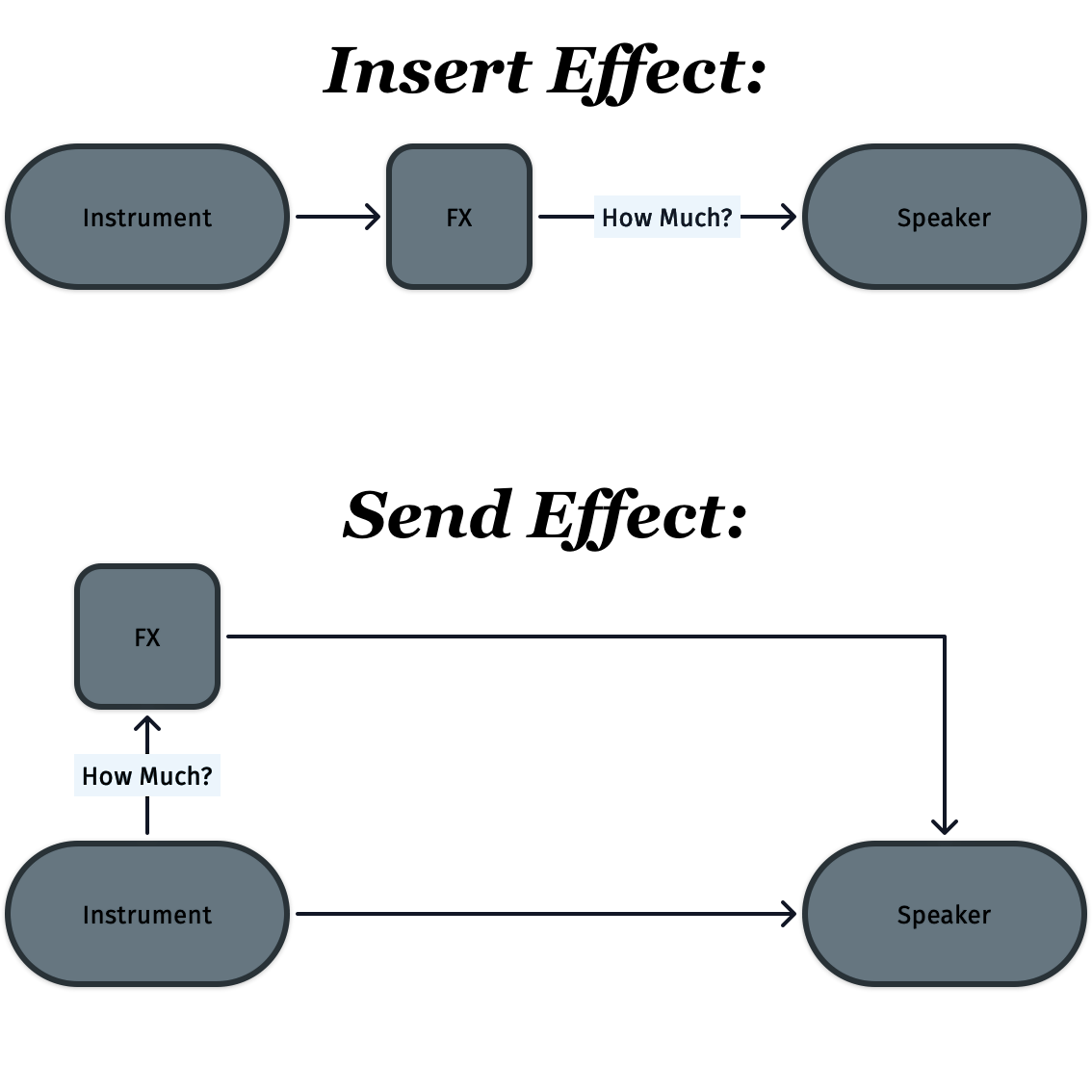

There are two main ways to route a signal into an effect; as an insert or as a send. These names come from the days of mixing consoles and so are a bit unintuitive, but the concepts behind them are pretty simple. As we can see (fig 1.1), it mostly comes down to where we ask “How much?”

An insert effect is one that “inserts” itself into the signal path — that is, it sits completely between the instrument and the output. No sound can go around it, all sound must go through it. This means it has an important decision to make; how much of the original vs. the affected sound should pass through? The answer is usually “¿Por qué no los dos?” (fig 1.2) and this is handled by mixing the two signals together.

A send effect, on the other hand, sits outside the signal path. It takes in some amount of signal, dutifully processes it, and passes it on to the output. As such, it doesn’t have any decisions to make. It’s the instrument that has to decide how much signal to send to it.

How They Sound

In some ways these two approaches are very similar. They both end up with some amount of the original signal from the instrument being played along with some amount of the affected signal from the FX. But where that “some amount” decision gets made is important to how the FX gets used as part of a chain vs. in a performance.

Say we have a reverb set up as an insert effect and play a chord on our instrument. All of that chord is hitting the reverb, always, all the time. Depending on how much of the affected signal we mix in, we may not hear the reverberations, but they’re there. That means we can set our mix to 0% affected sound, play our chord, then turn it up and hear the tails of our reverb come in. Conversely, if we play a chord again and turn the mix of affected sound down, our reverb tails would disappear.

Now assume the same setup, but our reverb is on a send instead of an insert. When we play our chord, only the amount of it we choose hits the reverb. So if we set our send to 0% and play a chord, we get no reverberations. Nothing hit the reverb do it didn’t make any sound. If we then turn our send up to 100%… we still hear no reverb. Turning up the amount sent after the fact doesn’t change anything. There’s still nothing there.

Conversely, if we set our send to 100% and play our chord, it’ll all hit the reverb and we’ll hear huge tails. If we now turn the send down to 0%, we’ll still hear those tails as they bounce around and decay. Turning down the amount sent to the reverb after the fact doesn’t change what’s already bouncing around in there.

What this Means for the Steampipe

Most of the time, FX are built into synths as inserts.1 When creating patches, it’s often easier to set the desired proportion of signals directly via a mix. Which is great when we want the FX to be integral to our preset.

But with an insert, we can’t decide which parts of our playing hit the FX. All of it always does. We only have control over how much of resulting FX are heard. So if we want to “play” the FX as an instrument — deciding which parts of our performance get sent to it how often and by how much — an insert isn’t going to cut it. We need to use a send.

So the reverb of the Steampipe is wired as send because it’s meant to be played as an instrument.

For example, the Steampipe’s reverb can have an absurdly long, essentially infinite decay. If it were an insert, there are very few situations in which we’d be able to take advantage of that because everything we played would hit the infinite decay of the reverb and we’d end up with a gooey mess.

But as a send, when our MIX is zero, nothing is contributing to that infinitely swirling space. Then we can pop up the MIX and play a chord. Only those notes enter the smear of the reverb. We can turn the MIX back down and still hear our infinitely decaying ambience. And, with MIX at zero again, no further notes we play will contribute to it, preventing it from blooming into muck.

It’s a fun way of working with reverb that feels particularly well suited to the Steampipe’s modeled, expressive, sometimes downright clangorous sounds. But is a bit unexpected. Hopes this clears up what’s going on for folks.

-

Citation needed. ↩︎